How to create rewards and narratives to master your habits beyond simple robotic routines 🤖

One more week on the calendar, and you realize you haven’t been working out as much as you’d like? 😅

It would be great if you could automatically put on your gym clothes and go to training without thinking twice 🏋️♀️ but your head keeps making up a thousand excuses to postpone exercising, right?

This internal struggle is common, even professional athletes report thinking “I don’t want to train today” — and go anyway. 💪

Even worse is when you go a long time without exercising. Resuming can be horrible — the body aches, the perspiration is intense, the heart is racing… 😓💦💔

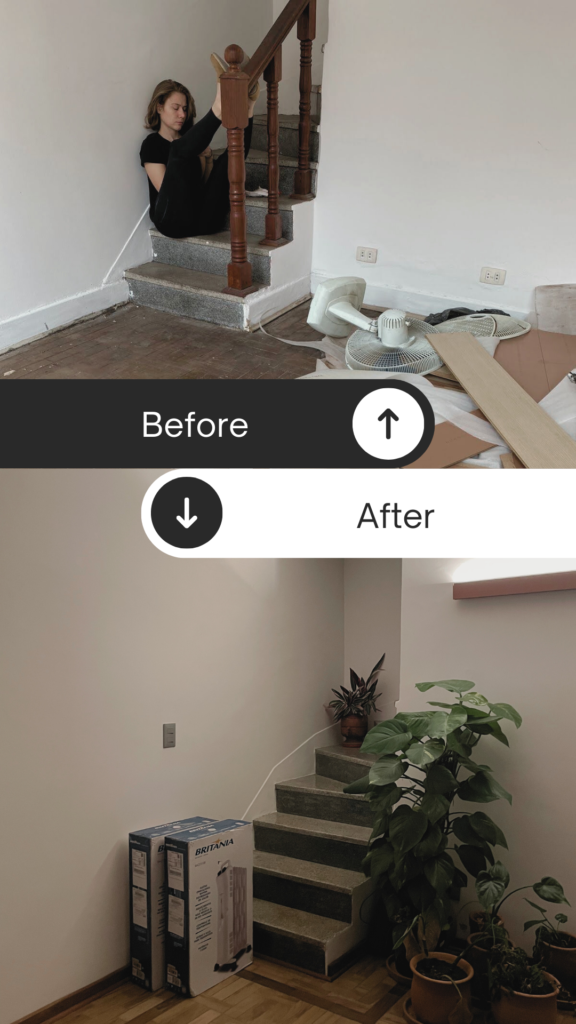

Creating a habit is getting through the first moment of awkwardness.

This initial stage can last for days, months or even years.

Establishing a habit involves consciously repeating something over and over again until memory recognizes that, after suffering, there is a worthwhile reward. 🔄🏆

So exercising goes from being just a habit or routine, to becoming a ritual. 🧙♀️✨

Habits and Routines

You’ve probably heard of the books “The Power of Habit” and “Atomic Habits”. Let’s recap the three essential components of a habit:

- Trigger

- Routine

- Reward

In the example of the gym, the trigger for going to work out could be a motivating playlist 🎶, leaving your gym clothes in a visible place 👕, or asking a friend to remind you. 📅

We’ll see more about routine and reward below later on.

The Hook Model

Large companies build habits for both employees and consumers, making their products and services part of everyone’s daily lives.

To do this, they generally use the hook model, which involves four phases:

Trigger: The starting point that prompts a behavior, an external stimulus such as emails or notifications that direct specific actions. 🔥 The purpose of the trigger is to instigate a simple run action.

Action: The user responds to the trigger by performing a known, simple task and then receives a reward for doing so. The simplicity of the action combined with the motivational drive plays a crucial role and facilitates the formation of this initial habit of the process. ✅🚀

Variable Reward: After the person performs the action, for example, clicking on a link, the reward that follows is variable. This unpredictability releases dopamine in the brain, making the hook cycle more addictive. This principle is common in slot machines and lottery games. 🎰🤑

Investment: Let’s assume that the user has registered on the site, dedicating time and effort to enter their information there. This process establishes more solid ties with the company and increases the probability of repeating the engagement cycle, that is, going back there to see the profile, buy from the website, etc. Other investment examples are:

create favorites lists,

meet the store owner,

close an annual plan,

have friends who go there,

follow famous people on a network,

learn new features of that platform… 💼📈

Note that it is similar to the trigger-system-reward system that we saw in the previous topic, but the unpredictability factor makes the method a little more powerful, so much so that it can make us addicted to bad habits for ourselves, as Fumio Sasaki reminds us:

“People who are encouraged by companies to work too hard may feel euphoria from self-sacrifice, working too hard is recognized by their peers, so their pain is its own reward (social approval). Even if they want to get out of that situation, it can be hard to isolate yourself from the corporate community.”

An easier way to create a new habit is to tie it to an existing one, creating a logical sequence of actions, as if it were a cake recipe.

Habit stacking

For example, whenever I make coffee, I’ll wash the dishes while the water runs out, then I’ll sit in the armchair — and leave a book there for me to read 10 pages — while I drink coffee. ☕📖

Gradually, these routines can evolve into ingrained habits in your daily life — even more so if they include addictive substances, such as coffee or cigarettes, which is also why it is difficult to break bad habits. 🚫🚬

Rituals

Rituals are meaningful practices charged with purpose and intention.

While routines are daily tasks that require conscious effort to maintain, rituals go beyond the mere completion of activities, they have greater meaning even when dealing with simple activities.

Here are some examples:

Cooking for the week, even just for you, can have a sense of community and service if you consider that each experience in the kitchen hones your cooking skills, allowing you to better serve your loved ones when you cook for them. 🍳👨🍳

The task of cleaning the house can transcend the action itself, turn into a moment of meditation or a ritual of internal and external purification if, for example, you commit to maintaining mindfulness and focusing on your ownBreathe throughout the cleansing process, breaking up stray mental patterns and providing mental clarity. 🏠🧘♀️

Going to the gym can turn into another act of service if you think of physical exercise as a means of strengthening your muscles, allowing you to become a stronger, healthier person to care for children and the elderly. 🏋️♂️👶👵

Rituals are intrinsically linked to your sense of identity.

This special link facilitates the formation of rituals, as we can see with followers of religions, people who see themselves as part of a country or school, for example, they see a relationship to doing certain activities with the group they belong to. 🙏 👥

No activity is special in itself or exclusive to a particular type or group of people. However, they gain this status when we build positive narratives around them. 🌟

Building a Custom Strategy — and Testing

By understanding the difference between habits, routines, and rituals, you are empowered to strategize and experiment with different approaches to incorporating habits into your life. This is similar to how companies test various strategies to build customer and employee loyalty. Here are examples for each concept we saw earlier:

Trigger: Set alarms for your desired activities and add unique ringtones to each one, creating a unique call to action.

Simple action: After the trigger, go do something simple, like drink a glass of water, wash your face, pet your pet, write a sentence of gratitude…

Unpredictability:

- on the task: Write down different types of physical exercises on small pieces of paper. Fold them and place them in a pot. After completing your simple action, grab a paper and go to training 💪

- on the reward: Still using the idea of the jar with pieces of paper, write rewards, after performing a task, choose one.

Investment: Call people to go to the same gym as you or commit to making a bond at the gym — with the receptionist or with the teachers — so you increase your bond with that place.

When something becomes a habit, it’s like we teach our mind to like a new reward. Sometimes we prefer things that give us quick satisfaction over waiting for something better in the future. It makes us avoid challenges and choose easy things.

Things that look cool will never go away.

Creating rituals is a journey to educate the brain to recognize that it’s not just a promise: the reward will SURELY come.

For this to happen, we need to repeat the activity many times, which strengthens the connections of synapses in our brain. Gradually, the brain records the information: there are bigger rewards ahead. Thus, activities of immediate pleasure lose their fun, little by little.

Now is the time to act. Identify the habits you want to cultivate and routines worthy of turning into rituals ✨

Finally, I leave you with a quote from Murakami in his book What I Talk About When I Talk About Running:

Certain processes do not admit variations. If you need to be part of the process, just transform — or perhaps distort — yourself through constant repetition, making the process a part of your own personality.

Pin this post