Rich neighborhoods very well delimited and far from the poorest, several subcenters that don’t talk to each other, have you ever had the impression that visiting São Paulo is like visiting many different cities?

The city has a disjointed and segregated formation, mainly the result of the adoption of foreign urban public policies, instead of having created our own policies based on our existing reality.

These policies were driven by foreign capital and were practices that created the financialization of land in other countries, forming a more complex real estate market.

As the policies prioritized the profit of some agents and not the better socialization of the population, as a consequence, there was the breakdown of community life, the super individualization of lives, the difficulty for all classes to connect, among other hallmarks of the capitalist system and hyperconsumption.

Even knowing that these policies generated social problems, the Basic Urban Plan (PUB), prepared in 1969 by a consortium between two Brazilian and two North American companies, included among its elements the same American practices that were sold as innovative measures to stimulate the urban development through subcenters.

Instead of enriching and strengthening the existing infrastructure in the city, new centers were artificially created, not because the population indicated this need, but to create spaces where new investors, mainly foreigners, could operate.

One of the emblematic cases was the corporate and financial center, which was previously located on Avenida Paulista and was driven by developers to be dispersed and built from scratch on the banks of the Pinheiros River.

In her Ph. adequate housing and relocation for these people.

This process is very similar to the zoning that expelled the poor from New York City in the 1920s: when the number of people in the city increased significantly, it forced different social classes to live very close to each other. Middle-class people, who had access to industrialized consumer goods, now no longer wanted contact with millions of poor and indigent people.

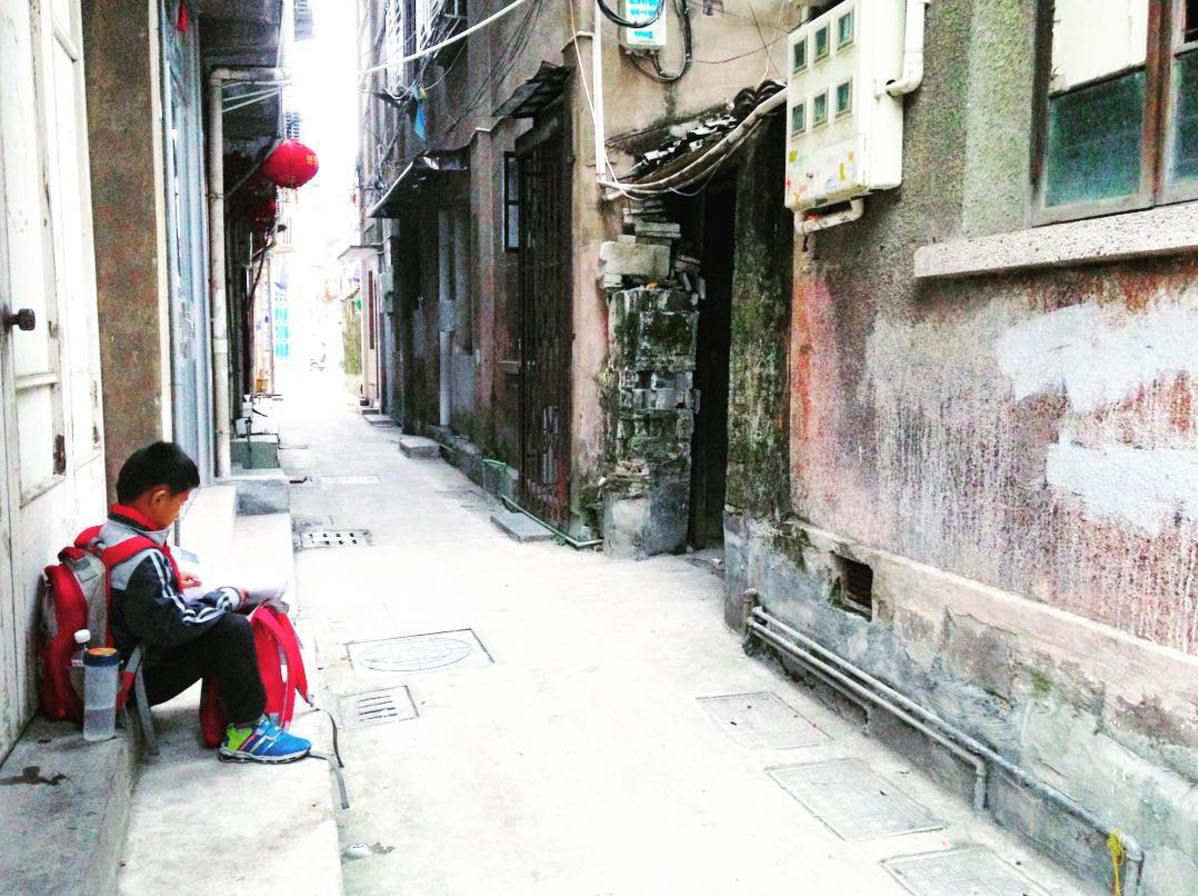

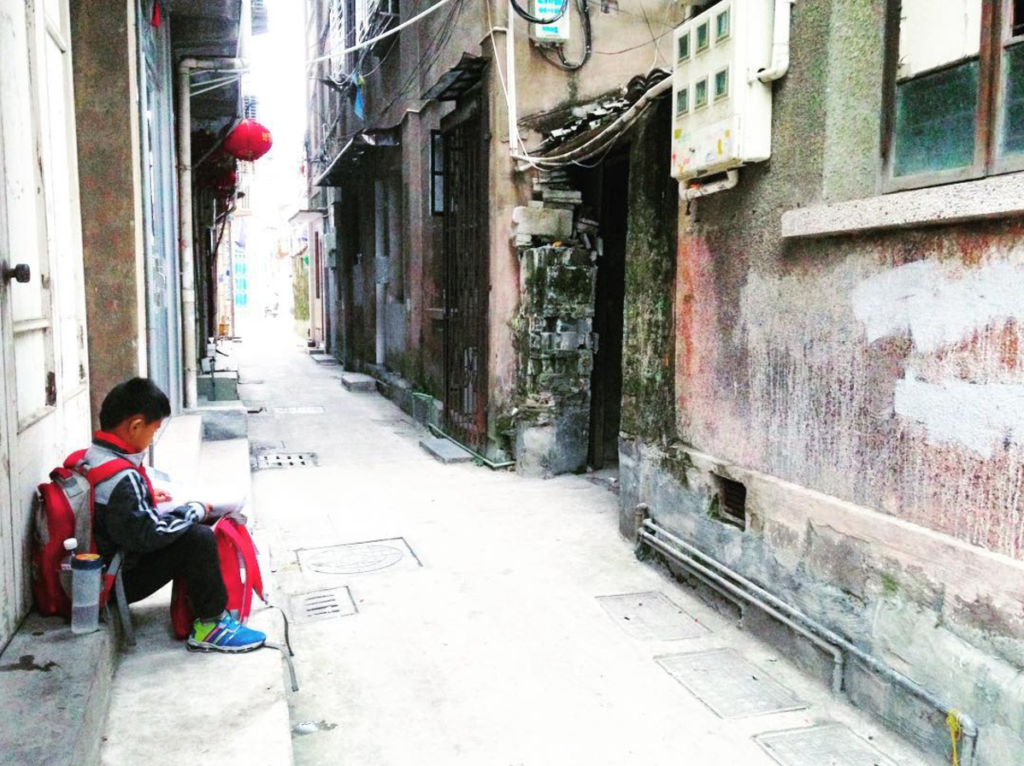

This started the process of gentrification or ennoblement of urban areas, done through higher taxation or definition of uses for each area, among other zoning tools that make it illegal or very expensive for the poor to be in certain districts of the city, these mechanisms bureaucratic led to the expropriation of the tenements and the poor were induced or forced to leave the centers and live in distant housing complexes or found other ways of (over)living by themselves, sometimes with access to mass transportation, the subway.

These urban decentralizing tendencies are considered by the sociologist Bauman — precursor of the concept of liquid modernity and who also thinks about urbanity in this key — as strategies that aim, purposefully, at the segregation and disintegration of community life, since coexistence in the city starts to depend on the Mobility and Time, two luxuries.

Thus, the city entered the 20th century. With the increase in wealth, there was a search for the materialization of comfort in the territory through demolitions, requalifications, landscaping and adequacy of spaces for transport.

On the other hand, part of the wealthy portion decided to move away from the centers and it is also at this time that the suburbs appeared: neighborhoods further away from the city center, but for richer people, generally composed of houses with a garden.

the suburb

In the United States, the pioneering city in this model was Los Angeles, described by Peter Hall as “the city by the side of the highway”, because the suburban neighborhoods were built where the ranches by the side of the road used to be. Those cheap, devalued lands were bought at a bargain price, separated into lots and sold as special, peaceful spaces for family homes.

That is, ranches adjacent to the city were intentionally purchased for real estate speculation. This decentralization model became a great opportunity for developers, it was a life project to be sold to the middle class public.

Around here, more than 50 years later, we copied the model: the Alphaville region was formerly land of traditional and wealthy families in São Paulo, but inhabited by a hundred small producers, the region began to be expropriated and divided into lots from the 1960s onwards. 50 and was launched as a product, a new concept in housing, in the early 70’s.

It didn’t happen that the rich naturally went there, the plan was ingenious to build a new independent urban core: there was a plan to induce people to actually live in these neighborhoods, the condominiums imposed strict rules for building permanent residences to prevent subdivisions become just vacation homes.

To attract these residents, advertisements made appeals such as “Verteville 4 — in Alphaville -, real solutions to current problems” or, as the psychoanalyst Dunker brings in his book on Alphaville “Mal-Estar, Suffering and Symptom: A psychopathology of Brazil between walls”, condominium advertisements are even more explicit: “Vila das Mercês. The right not to be disturbed”.

At the time, articles for the newspaper Estadão, Alphaville is stated as a neighborhood that overcomes the “embarrassment” of the chaos of the city, among other speeches similar to those of the promises in Los Angeles in the 20s-30s, condominiums that would be the “construction of authentic communities”, an oasis of collaboration, protected by private security.

It is not known, however, where such high expectations of advertisements came from, as the housing model in suburbs had not worked in Los Angeles, which suffered impacts as early as 1920.

In his book “City of Quartz”, Mike Davis discusses the decline of the city with the decline of commerce in pre-highway areas, the segregation of recreational facilities, the closing of community centers and the increase in street violence.

Here in Alphaville, the consequences can be clearly seen in the documentary “from the inside of the wall”:

In his book “Confidence and fear in the city”, Bauman defends the need for an urbanization that creates communities without walls, even though it is known that this urban integration is a permanent clash, an eternal struggle of interests.

Didn’t the propaganda say the poor were going to stay away?

In the decades following these decentralization movements in the city of São Paulo, social differentiation in became increasingly evident due to the location where people transit, mainly due to the relationship with individual purchasing power, which brought striking consequences for Brazilian society.

In 2001, Alphaville received an additional barrier with the inauguration of the first toll booth in the region, located on the Castelo Branco Highway, a few kilometers from the neighborhood.

This measure was met with criticism, because residents of neighboring cities had waited a long time for a faster route to go to São Paulo and, now that it was available, they could not use it due to the high abusive amount charged in tolls, which only thought of profiting from on top of the rich in Alphaville or, in a double movement, push the poor from that neighborhood even further away.

In São Paulo, we saw social segregation intensify, as with private security, walls and electric fences monitored by cameras and other new technologies.

In 2008 the mechanisms were even more subtle and far-fetched, when, at the inauguration of Shopping Cidade Jardim, the city was faced with a novelty: there was no entrance for pedestrians, to avoid those who did not have cars and, moreover, there was no square food at the mall.

Two years later, between 2010 and 2011, residents of the wealthy Higienópolis neighborhood, with less than 5,000 inhabitants, opposed the construction of the subway line in the region, as they believed that this would bring “unwanted people”.

A resident of the neighborhood said, in an interview, that they were “different people”. The dispute for the territories materializes a few weeks later, in response, hundreds of people came together via the internet to hold a barbecue as a protest against the segregationist stance of some residents of the neighborhood, known as “Churrasco da Gente Diferenciada”.

In 2014, the issue related to the low-income population’s access to shopping centers was again highlighted in the media with the well-known “rolezinhos”. In them, low-income young people agreed to go in groups to the most expensive malls in the city, where before they were usually expelled when they went alone, separately. At the time, a well-known columnist ended up highlighting even more the prejudices rooted in society, saying that these young people were “incapable of recognizing their limitation and were jealous of wealthy youth, wealth and educated people”.

In 2019, another criticism surfaced when a famous person said that the airport was becoming a bus station, shamelessly exposing that he considered the clothes and mannerisms of the poorest people inappropriate for environments that until then were only frequented by the richest, like the airport.

Cologne 2.0

It is clear that many of these class conflicts are just a continuation of a society with a history of slavery, where the separation between the main house and the slave quarters becomes even more refined. Added to this, we have a scenario of globalization that induces the continuation of Brazilian submission to stronger economies, keeping the country in a position of colony, but with more refined economic-cultural-political mechanisms as well.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Brazil quickly entered the industrialized international market. However, during the second industrial revolution, countries like the United States and Germany invested heavily in research that generated new, more refined production technologies, increasing international competitiveness. Economist Wilson Cano argues that, at that time, the investment needed for Brazil to reach international levels in new technologies and scale of production was greater than what the Brazilian state could organize.

Foreign capital then enters under the pretext of modernizing what already existed and industrial policies are open to this, leading to the dismantling of various sectors, opening up even more space for foreign capital to denationalize the financial system. This scenario made it impossible for Brazil to become an independent neoliberal country.

In this scenario, São Paulo, the corporate capital of the country, seeks to become a modern and attractive city for investments by foreign companies, which come to “replace” the now obsolete and outdated Brazilian industry.

For this, it adopts public urban planning policies in the United States, such as “cities for cars” and “zoning plan”. This dynamizes capital and complicates the real estate market, still incipient in the city.

As a consequence, we observe an increase in the physical distance between those who can and cannot buy, live and visit areas of the city. The land, the territory and the city, now, are no longer places for coexistence, but products to be bought and financed by foreign capital.

None of this came as a surprise, as the US land planning models implemented did not promote socializing and community, but opened up a huge market for real estate developers. By bringing these models to Brazil, the side effects of such policies had been known for decades, but the weak economy made the dispute between foreign capital and state power unfair.