Yoga is a practice that has captivated people for centuries, and although many believe its origins date back to ancient India, its evolution over time is a story of exchange and invention. While we honor the traditions of the past, we also celebrate the dynamic evolution of yoga as a living practice that continues to inspire and transform lives.

Some of the developments in yoga occurred in the last century as a result of ongoing cultural exchanges, reflections of the onset of globalization. By the end of the century, scholars from all over the world joined the quest to discover the origins of this global phenomenon — whether through linguistics, history, archaeology, anthropology, sociology, among other areas of knowledge.

What they have discovered so far is that the tradition of hatha yoga initially had only meditation poses, cleansing practices, celibacy to obtain supernatural powers, and static physical postures, which were performed for hours and considered forms of austerity (“tapas”).

A historical account of the practice of “tapas” comes from the legendary Alexander the Great (356 BC — 323 BC), who encountered yogi ascetics on his travels. Alexander and his caravan were surprised to see men motionless under the scorching sun, apparently possessing superhuman powers to withstand the hot ground under their bare feet.

His encounter with the yogis was a cultural shock; he had never witnessed such a demonstration of mental and physical discipline. Here is an excerpt from his accounts:

“[…] Another was on one leg, with a three-cubit-long piece of wood raised in both hands; when one leg was tired, he changed the support to the other, and so continued all day” — Roots of Yoga, Mallinson and Singleton (2017: 88)

From then on, much has changed, and it is interesting to note that hatha yoga texts were influenced by bodily practices from other places. Below I list some texts and the number of postures described in them:

- 12th century; Dattätreyayogasästra; 1 posture

- 13/14th century; Vivekamärtanda; 2 postures

- 13/14th century; Goraksasataka; 2 postures

- 15th century; Sivasamhità; 4 postures

- 15th century; Hathapradipikä; 15 postures

- 18th century; Hathapradipika-Siddhäntamuktävali; 96 postures

- 18th century; Gherandasamhitä; 32 postures

- 18th century; Jogapradipyaka; 84 postures

- 1966; Yogadipika by BKS Iyengar (“Light on Yoga”); 200 postures

Although the early texts had few postures, by this time in ancient India, there were already several sequences described, but in other contexts, such as in Jain scriptures, the Upanishads, the Mahabharata and Ramayana Epics, the Puranas, and the Pali Canon of the Theravada Buddhist tradition.

They are also in Tantric texts, for example, the Pasupatasutra prescribes dance as part of the worship of Pasupati, while the Nayasutra of the Nisväsatattvasamhita teaches the practitioner how to reproduce the forms of the alphabet letters with bodily postures.

All these strands may have influenced hatha yoga later on, but it is worth remembering that the exchange between India and other countries has always existed, and we can draw other parallels as well:

Note that the increase in postures occurred from the 15th century, which may be connected with the growing interest in male beauty after the Middle Ages. At this time, Michelangelo sculpted the statue of David, and many discoveries were made about anatomy, biomechanics, and muscle kinesiology, trends that may have come into contact with Indian lands.

The case of the Sun Salutation — Surya Namaskar

For decades, the Sun Salutation sequence has been practiced in yoga studios worldwide, with many assuming it to be a series of movements from ancient Hatha Yoga texts. However, the truth is that none of the texts, images, or sculptures discovered to date mention this sequence.

Despite its popularity, the origins of this practice are often neglected in yoga teacher training. Surya Namaskar A, B, or any other variation practiced in yoga studios was created less than 100 years ago by Indians looking for a “complete” physical exercise and was then incorporated into Hatha Yoga, its popularity boosted by both yoga gurus and bodybuilders.

I explain, during World War I and II, showing health and strength was a way to demonstrate national sovereignty. For example, the Germans used their gymnastic exercises not only to develop healthy bodies but also to promote morality and create “new Germans.”

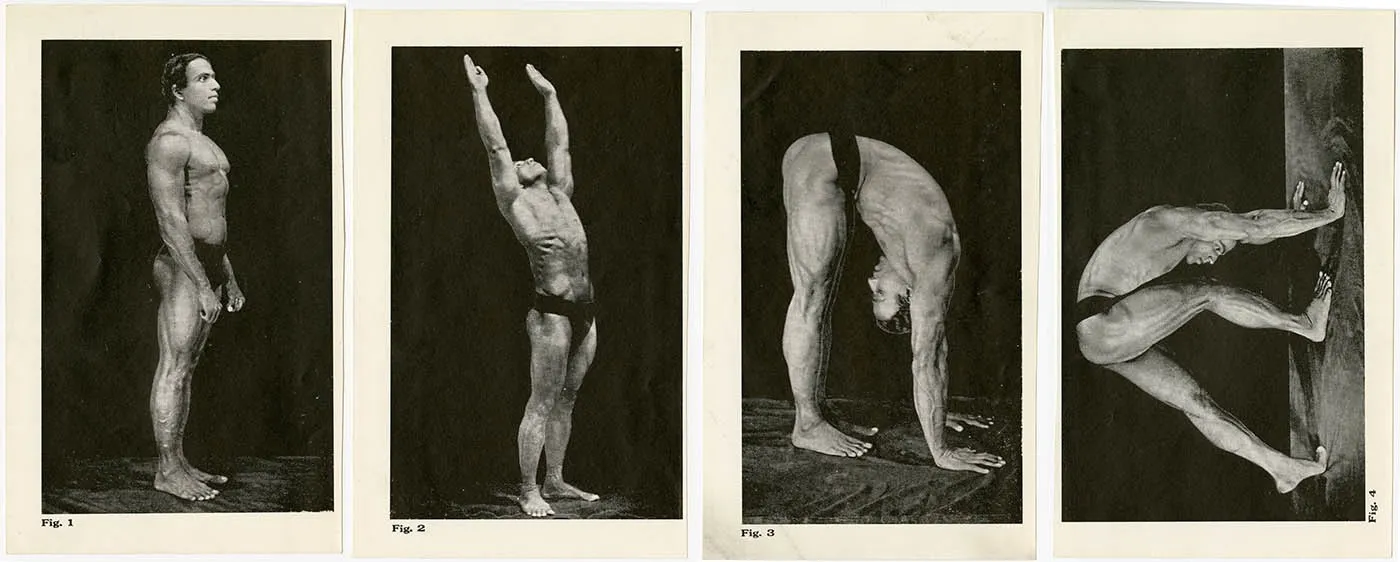

In Europe, various texts on sports such as rowing, horseback riding, boxing, and swimming, as well as manuals on walking, climbing, and jumping, were published at this time. In this context, health and fitness magazines emerged, such as L’Athlète, which debuted in 1896, the same year as the first modern Olympic Games. In 1893, the first international bodybuilding exhibition also took place:

In India, various Western gymnastics like Ling, Sandow, and YMCA had a significant impact and were incorporated into the local culture of fights. This influence is evident in The Indian Encyclopedia of Bodybuilding (1950), a book that was translated into English and sold in other countries, and which included a description of Surya Namaskar as an exercise, along with a detailed history of the tradition.

This history of Surya was probably inspired by what was written in Yoga-Mimansa, the internationally famous book by Kuvalayananda (1920), where the author narrates that young Brahmins of the 18th century used to perform up to 1,200 sun salutations every morning. This information, however, has never been found in any other historical or religious account. Kuvalayananda probably used this story to promote his technique as more traditional and original than other manuals, a common marketing tactic at the time.

In reality, Surya Namaskar was created by a wealthy and powerful Rajah of Aundh, a region near Bombay. After trying other exercise manuals and not achieving the physical goals he hoped for (who hasn’t?), he created his sequence of postures from some movements he saw his father do when young and, with the help of guru Paramahansa Yogananda, adapted it as a form of gymnastics for the general public.

According to the book by Elliott Goldberg “The Path of Modern Yoga: The History of an Embodied Spiritual Practice,” Bhawanrao Shriniwasrao Pant Pratinidhi (1868–1951), also known as Bala Sahib, was an Indian political leader who popularized the practice of the Sun Salutation in the early 20th century and founded a school of yoga and gymnastics in Satara, India, where he taught the Sun Salutation as part of the curriculum.

Bhavanaro probably named his sequence Surya Namaskar due to its resemblance to the sun worship ritual in which Brahmin priests kneel and prostrate — a ritual that can still be seen today at the Sun Temple in Andhra Pradesh.

However, Bhavanaro and Yogananda’s sequence does not include the “Om” mantra, the “Gayatri” mantra, or any other prayer, which are usually part of the sun worship ritual. The sequence is purely physical and is not intended to be a spiritual practice, although it has been incorporated into the Hatha Yoga tradition as such.

There was a booklet — like other manuals of the time — that included illustrations and recommended practices in cycles, ranging from 25 to 50 cycles for children aged eight to twelve, 50 to 150 cycles for boys and girls aged twelve to sixteen, and 300 cycles for everyone over sixteen.

After becoming popular in some regions of India, this sequence was disseminated worldwide, both in the bodybuilding book and in Kuvalayananda’s book mentioned above, but generally inserted into mediums related to Yoga.

The practice navigated between these two worlds probably because the nationalist or anti-colonialist propaganda of the time suggested that God desired healthy bodies for the nation and emphasized the importance of developing physically, as well as mentally, morally, and spiritually strong Indian youth.

Thus, the practices were all performed in the same gyms (known as akharas), where practitioners shared various techniques. In these places, there were strong anti-colonialist movements, creating a paradox between accepting European and foreign techniques in general, but at the same time strengthening the nationalist movement. Therefore, sometimes everything was appropriated, adapted, and renamed as a “purely Indian” practice — sometimes placed under the umbrella of yoga.

It is also interesting to note that this holistic view (body, mind, consciousness, and religiosity being interconnected) already comes from Indian culture, and it is possible to find in medieval hatha yoga texts descriptions of various things called “yoga” and the reproduction of these same concepts compiled later, centuries later, in other texts, also as yoga.

In more modern cases, there are texts reporting, for example, the practices of Iyer, a world-renowned Indian bodybuilder, who incorporated religious pujas and hatha yoga cleansing practices into his gym training routine. Similarly, Bhavanaro himself performed Surya Namaskar daily between 3 and 4 in the morning, chanting Vedic and bija mantras.

The fusion of yoga and bodybuilding is perhaps best exemplified by the Bishnu Charan Ghosh Cup, an annual yoga competition held in Los Angeles. The event is named after Bishnu Charan Ghosh, a famous Bengali bodybuilder and founder of the Calcutta College of Physical Education (1923), now known as Ghosh’s Yoga College.

Ghosh was none other than the younger brother of Paramahamsa Yogananda, author of the iconic “Autobiography of a Yogi” and co-author of the Surya Namaskar sequence with Bhavanaro, as mentioned earlier.

After just a few decades, the relationship between yoga and bodybuilding seems to have been forgotten, with many online videos portraying the two practices as total conflicting opposites. However, a closer examination of history reveals that these two disciplines would be very different if they had never crossed paths.

As we have seen, the wave of bodybuilding influenced the creation of the Surya Namaskar sequence, which was later incorporated into the repertoire of Hatha Yoga and is now practiced as a meditation in sync with breathing.

Another example of the ongoing exchange between yoga and bodybuilding is the stomach vacuum, a cleansing technique described in medieval yoga texts known as “nauli,” which was incorporated by bodybuilders and is still practiced today.

If you are interested in studying other connections like these, the online study platform Yogic Studies offers university-level courses to explore yoga, Indology, and South Asian studies. The platform is a unique place where scholars from around the world offer modules in their areas of expertise. It’s an opportunity to explore the rich history and culture of yoga, its relationship with other disciplines, and historical moments.

Click here to get 7 free days on the platform .

*Curious fact: fascists and Nazis loved yoga (or what was disseminated as yoga).

Pin this post

Leave a Reply